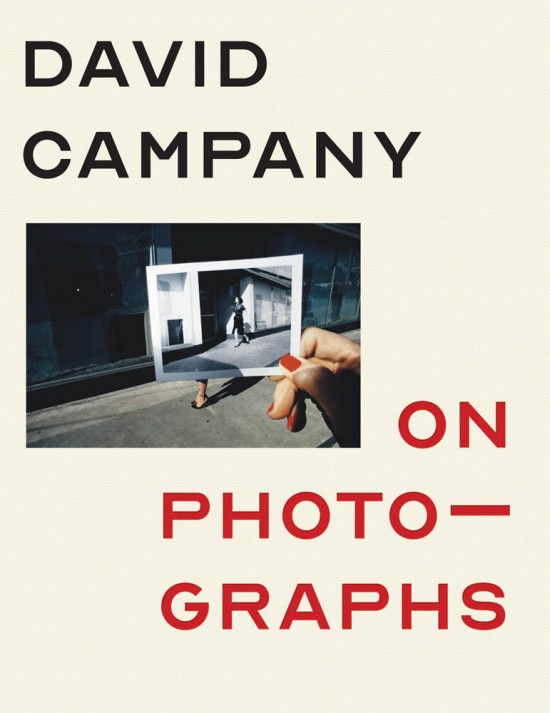

David Campany: On Photographs

David Campany: On Photographs

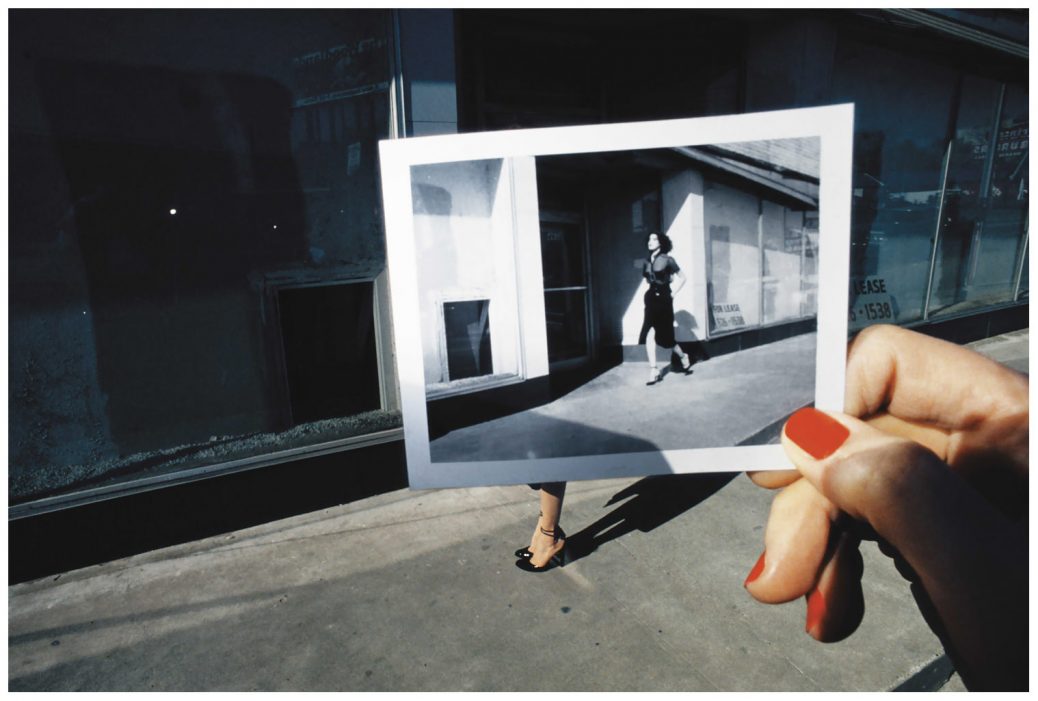

In On Photographs, curator and writer David Campany presents an exploration of photography in 120 photographs. Proceeding not by chronology or genre or photographer, Campany’s eclectic selection unfolds according to its own logic.

We see work by Henri Cartier-Bresson, William Eggleston, Helen Levitt, Garry Winogrand, Louise Lawler, Andreas Gursky, and Rineke Dijkstra. There is fashion photography by William Klein, one of Vivian Maier’s contact sheets, and a carefully staged scene by Gregory Crewdson, as well as images culled from magazines and advertisements.

Each of the 120 photographs is accompanied by Campany’s lucid and incisive commentary, considering the history of that image and its creator, interpreting its content and meaning, and connecting and contextualizing it within visual culture. Image by image, we absorb and appreciate Campany’s complex yet playful take on photography and its history.

The title, On Photographs, alludes to Susan Sontag’s influential and groundbreaking On Photography. As an undergraduate, Campany met Sontag and questioned her assessment of photography without including specific photographs. Sontag graciously suggested that someday Campany could write his own book on the subject, titled On Photographs. Now he has.

Forthcoming, 2020. Published by Thames & Hudson in the UK, MIT Press in the USA, Guilio Einaudi Editore in Italy.

An extract from the introduction to On Photographs

“Photographs are often thought of as ways to hold things still, to calm the flux of a restless world. They allow us to gaze at fixed appearances, for pleasure or knowledge, or both. But very little else about them could be described as ‘still’. From the beginning, photography’s technologies have been in a state of constant change and development, and the tasks we have given the medium have continued to mutate and expand beyond measure. Moreover, the photographs are highly mobile. They move over time, across culture, and between contexts. They lose meanings and acquire meanings. Indeed, they could not be quite so mobile were they not quite so fixed. The mute stillness of photographs permits their promiscuity and proliferation. And so, paradoxically, photographs have helped to produce the flux they promise to calm. They confuse as much as fascinate, conceal as much as reveal, distract as much as compelling. They are unpredictable communicators. They cannot carry meanings in any straightforward way. A single photograph is unable to account for the appearance it describes, or even account for itself. Like Herman Melville’s Bartleby, a photograph is insistently there, but enigmatic. In each one there is a kind of madness.

All of this leaves photography open to those wanting to take charge of it, to use it in one way or another. Broadly, there are two ways this happens. The first is to give photography pictorial conventions. Images that follow a formula are less likely to surprise and will give the impression of meeting needs and expectations, of being ‘functional’. Through the convention, photography masks its madness. The second way is to accompany photographs with words. Writing, speech, discourse. Think of the complex legal system that secures the status of the police photo, or the connoisseur declaring this photograph better than that; the advertisement making claims in words for a product it depicts; the returning tourist narrating their vacation photos to friends; the caption for a news picture; or the photographic artist stating their intentions. The image cannot achieve any of this by itself. Words do many things for photographs, but in general, they are used to oversee and direct them, the way parents supervise wayward children. Photographs can be bent to limitless wills, but never precisely so. They always have the potential to exceed the demands imposed upon them. And in that excess, photographs work upon us in ways we still barely comprehend.

If a photograph compels, if it holds our attention, it will be for more than one reason. The reasons may be unexpected, and even contradictory (mixed feelings are often the most compelling). When we are drawn to look at a photograph, again and again, it is likely that our second or third response will not be quite the same as the first. Of course, most photographs do not stay in the mind for long at all, but this does not mean we can predict which ones will, or why, or whether a brief encounter with an image will leave some ineffable mark upon us. Photographs need less explanation than our responses to them.”

About the Author

David Campany is a curator, writer, and Managing Director of Programs at the International Center of Photography, New York.

Renowned for his engaging and rigorous writing, exhibitions and public speaking, David has worked worldwide with institutions including MoMA New York, Tate, Whitechapel Gallery London, Centre Pompidou, Le Bal Paris, Stedelijk Museum, The Photographer’s Gallery London, ParisPhoto, PhotoLondon, The National Portrait Gallery London, Aperture, Steidl, MIT Press, Thames & Hudson, MACK and Frieze.

In 2020 he curated the three-city Biennale für Aktuelle Fotografie 2020 – The Lives and Loves of Images (Mannheim/Ludwigshafen/Heidelberg, Germany).

Recent curatorial projects include Alex Majoli: SCENE (Le Bal, Paris, 2019); The Still Point of the Turning World: Between Film and Photography (FoMu Antwerp, 2017); The Open Road: photography and the American road trip (various venues, USA, 2016-); A Handful Dust (Le Bal, Paris, 2015; Pratt Institute New York, 2016; the Whitechapel Gallery London, 2017; The California Museum of Photography, 2018; Polygon Gallery, Vancouver, 2019); Walker Evans: the magazine work (various venues – France, Poland, Belgium, Italy, Australia and New Zealand, 2014-2017), Lewis Baltz: Common Objects (Le Bal, Paris 2014); Victor Burgin: A Sense of Place (AmbikaP3 London, 2013); Mark Neville: Deeds Not Words (The Photographers’ Gallery London, 2013); and Anonymes: Unnamed America in Photography and Film (Le Bal Paris, 2010).

David’s many books include On Photographs (2020), So Present, So Invisible – conversations on photography (2018), A Handful of Dust (2015), The Open Road: photography and the American road trip (2014), Walker Evans: the magazine work (2014), Gasoline (2013), Jeff Wall: Picture for Women (2010), Photography and Cinema (2008) and Art and Photography (2003).

He has written over two hundred essays for monographs and museums. He contributes to Frieze, Aperture, Source, and Tate magazines.

David has a PhD. For his writing, he has received the ICP Infinity Award, the Kraszna-Krausz Book Award, the Alice Award, a Deutscher Fotobuchpreis, and the Royal Photographic Society award.